A few days before the Weston Theater Company in Vermont was set to open its production of "," production stage manager Michele Kay stood off stage, still trying to figure out how to position the actors and props.

“Can’t we just take the couch to the left, like in front of the piano?” she asked, as the actors moved a little to the right and left, and a stage hand slid the couch across the floor.

This theater is not where they were planning to put on the musical. It was supposed to open at the playhouse up the road, where the company has been putting on plays since 1937. But in July, the old theater flooded, one of the many buildings hit by .

Weston Theater Company artistic director Susanna Gellert says the riverside theater has flooded before, but this time .

“The entire basement of the playhouse was flooded through the ceiling,” she said. “And the water came through the ceiling, through the orchestra pit, into our audience.”

The last time the playhouse flooded, from Tropical Storm Irene in 2011, the company was able to clean up and dry out in time to get their production back on to the big stage.

The damage this time around.

As climate change threatens to cause more flooding, more often, the company is still deciding how and whether to rebuild, Gellert said.

“Normally at this time of year, I would be starting to plan next season,” Gellert said. “I actually was in the midst of planning for next season when this happened. And this is somewhat on hold right now while we do the modeling and think about what’s next.”

Summer is a crucial time of year for New England’s local theater companies. Their productions bring delight, crowds and tourist dollars. And they’re facing challenges as the region’s climate changes.

Extreme weather forces new policies

In July, as part of , a theater company staged “The Tragedy of Macbeth” on a lawn at the University of Saint Joseph, in West Hartford, ���ϳԹ���.

Attendees gathered for one of the final performances on a day when temperatures topped 90 degrees.

“It's actually easier on stage than it is backstage,” said Kiera Sheehan, who played Lady Macbeth. “When you're on stage, you're so focused in the moment that I personally don't notice the heat or the sun. But as soon as you go backstage, it hits you.”

. And while it is a tradition to perform Shakepeare outdoors, today’s weather conditions are quite different from when the plays were written.

Shakespeare’s England in the 1600s was colder than it is today – in part from in the Northern Hemisphere. That was also hundreds of years before .

with human-driven climate change.

Stephen Young, a professor at Salem State University, says that will lead to more extreme weather.

“We're seeing these incredible floods because now the atmosphere can hold so much more moisture, that when the water comes out of the atmosphere, a lot more water comes out. And that is only going to increase,” Young said.

Backstage at “Macbeth,” there was plenty of water and ice packs. The costumes were lightweight, and it helped that many of the actors were wearing kilts. Along with the heat, this summer the company also navigated concerns about from wildfire smoke, and a lot of rain.

According to the Northeast Regional Climate Center, , with many areas seeing over 200% of the normal precipitation. Hartford, ���ϳԹ��� experienced its rainiest July on record.

The Capital Classics Theater Company has developed a policy for dealing with the weather. ”Macbeth” director Geoffrey Sheehan says the production will move to a nearby indoor theater on campus if there’s lightning, rain for more than two minutes, or temperatures above 95 degrees. This year, an air quality index was added to the mix.

Sometimes, the company has had to make the call to move indoors mid-performance.

Kiera Sheehan, who is the daughter of Geoffrey Sheehan, says they’re thankful to have a back-up plan.

“A lot of theaters unfortunately have to cancel. And we're very lucky that we don't,” she said. “We can just pick everything up and move inside and pick up right where we left off.”

Geoffrey Sheehan says audiences love outdoor theater, and they will put up with a lot for it.

He says safety for all is the priority.

“And at this point, we can continue moving forward,” he said. “With concern, paying attention, believing science, and working with it, is what we need to do.”

Not the final curtain

Many other theater organizations are working to address similar issues, according to Corinna Schulenburg, a spokesperson with the National Theatre Communications Group. This includes reviewing their investments in fossil fuels, building more sustainable sets, and choosing plays that address the climate crisis.

“We as theater makers have a real power — we’re story tellers, we’re culture makers — we have a real power to give people hope, to plug people into action, [and] to do it in ways that feel joyful and exciting,” Schulenburg said.

As she was preparing to perform a lead role in the Weston Theater Company’s production of "Singing in the Rain," Cameron Hill, a New York-based actor, remembers watching Vermont’s flooding unfold on social media and wondering if the show would go on at all.

The production team was able to move to the company’s smaller building down the street, which is about half the size of the one damaged in the flood.

“They’ve painted these floors at 2 a.m. They’ve been working double, triple overtime,” Hill said. “Everyone has put so much into making this possible.”

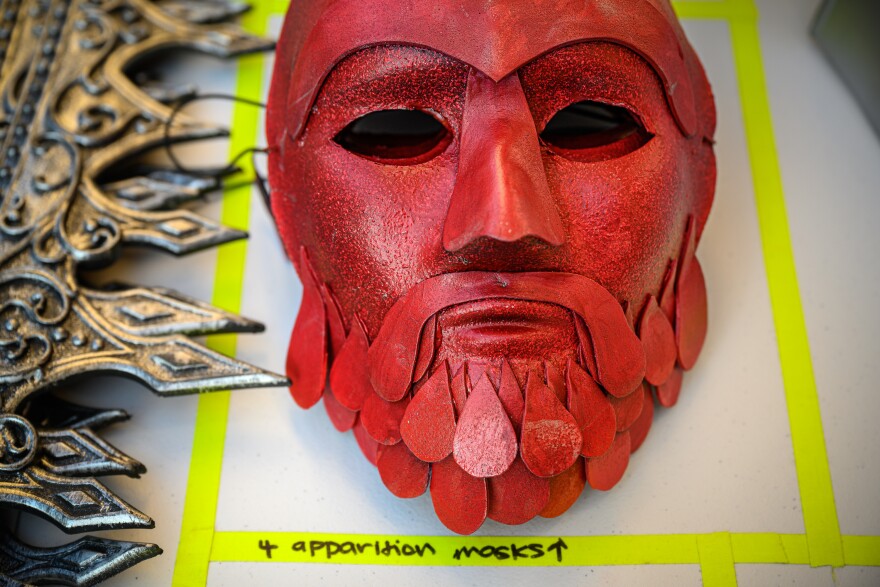

They had to make other changes, including using the lobby as the backstage, but "Singing in the Rain" is, after all, a story of resilience.

It’s a story of how a group of silent film actors adapt to the changing world of talking pictures.

And while the theater company figures out how to adapt to climate change, for a few nights this summer anyway, they were singing.

Patrick Skahill of ���ϳԹ��� and J.D. Allen of WSHU also contributed to this story. Peter Engisch of Vermont Public mixed the audio version.