Tributes have cascaded in since Sidney Poitier died last week at 94. And so they should have. He was, as many have noted, an unparalleled actor, a committed activist, and a beloved family member. He was also, frankly, a heartthrob – quite literally tall, dark and handsome.

Poitier first became a movie star in the 1950s – an era where most of the Black men in movies and on television had little choice as to how they were portrayed. Some were silly (see Amos 'n Andy — the TV show, not the radio) or dim (Stepin Fetchit) or cast to be white-people-friendly. (Louis Armstrong was a musical genius and a race man, but in the 60s and 70s his Cheshire Cat grin was an embarrassment to many people my age; it seemed obsequious to young people newly enamored of Black nationalism.) Sidney was none of that.

Even as a little girl, I could see why our Negro mothers swooned. He was lithe, panther-graceful, with a smile that was sometimes private, sometimes completely, blindingly bright. I remember my mother's cast album of the movie Porgy and Bess; even as a character forced to move about on his knees, Sidney projected strength (But not with his singing voice; he was tone-deaf, so was dubbed by the great baritone Robert McFerrin, father to another musician who urged us Don't Worry, Be Happy...)

Whether he was a runaway convict (The Defiant Ones), a striver trying to move his family to a better neighborhood (A Raisin in the Sun) or an itinerant handyman building a "shapel" for a bossy German nun in the middle of the desert (Lilies of the Field), he was always upright, always Sidney. Even when it might have cost him his career., and later, the. At his own peril. On his own dime. Of course our mothers had to flock to the movies to support him.

Especially in movies like Paris Blues, For Love of Ivy and A Warm December, where he fell in love with women who looked like them. Many of them were less enthusiastic about Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, in part because Poitier's character, a Nobel-nominated physician, seemed to have partnered with a white woman, yes, but one who seemed pretty clueless about. (Remember, the movie debuted in the same year interracial marriage had become legal in all 50 states.)

When he became the, Poitier strode to the podium in white tie and tails, navigating through a sea of well-wishers and thunderous applause. He accepted with a brief, mildly giddy speech that was full of humility and delight. Almost 40 years later, in 2002, he accepted another Oscar, an honorary one, and thanked the "brave visionaries" who took a chance on him earlier in his career: "I benefited from their effort, the industry benefited from their effort, America benefited from their effort," he told the onlookers.

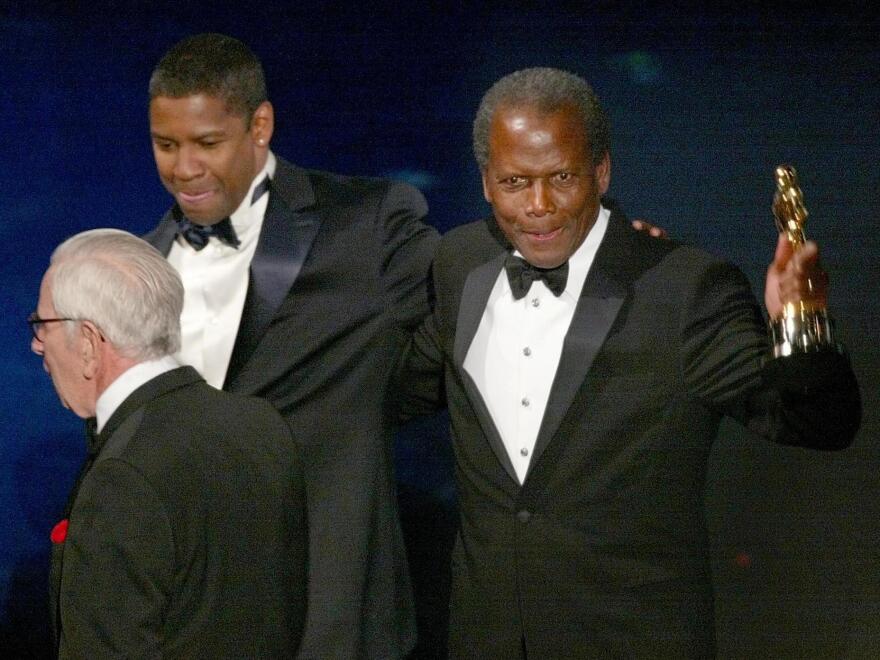

That night, the audience glittered with A-listers—including one of his mentees, Denzel Washington, who presented the award to him. The pairing was especially appropriate since that night, Washington became the second Black man ever to win a Best Actor Oscar for his lead in the police thriller Training Day. It was the same evening Halle Berry became the first Black woman to win an Oscar for Best Actress in Monster's Ball. Three Black Oscar winners in one night! When he accepted his award, Denzel Washington looked up at the box where Sidney Poitier sat with his family and saluted him—and. It was a moment.

That particular moment had a lot of Black folks of all ages swooning, these two handsome, accomplished Black men who had done so much to broaden America's narrow vision of Black manhood on film. But as my mother archly pointed out to me that evening, "Sidney was the first." True enough. The others—Billy Dee! Denzel! Will! Idris!—were able to follow because there was a Sidney. By insisting on being true to himself, he'd changed the cinematic landscape of what was possible. And for that, we thank him.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.