Jeremy Clark is walking through a section of ║┌┴Ž│į╣Ž═°ŌĆÖs Housatonic State Forest thatŌĆÖs had a rough couple of years.

ŌĆ£Most of the trees are dead,ŌĆØ Clark says, pointing out the telltale signs. ŌĆ£You can see all these oak trees basically have limited [or] no small, fine branches on them.ŌĆØ

It was about four years ago when Clark, the lead forester here, realized he had a problem on his hands. He was walking the woods, drawing up a forest management plan.

ŌĆ£I was actually out inventorying when I first noticed the caterpillars in 2021 falling on me, and I was like, ŌĆśThis is not good,ŌĆÖŌĆØ he recounts.

The black, bristly caterpillars raining down on him were young spongy moth larvae. TheyŌĆÖre a longstanding invasive insect with a . In their larval stage, the bugs are ravenous ŌĆō and they love oak. They can devastate an oak forest.┬Ā

They can leave woodlands more susceptible to fire. Within their range ŌĆō which encompasses all of New England ŌĆō theyŌĆÖve done to trees. Here in this forest, they stressed or killed up to 90 percent of the oaks in some sections.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs always amazing to see how much damage such a tiny insect can cause on a single tree and a whole forest,ŌĆØ Clark says. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs impressive.ŌĆØ

How it got here

The spongy moth, native to Europe, originally landed in North America in the 1800s, brought to Massachusetts by an amateur entomologist.

ŌĆ£It was a Frenchman,ŌĆØ explains Gale Ridge, an entomologist at the ║┌┴Ž│į╣Ž═° Agricultural Experiment Station. ŌĆ£In 1869, he brought the spongy moth in from England, wanting to crossbreed it with silk moths here in the United States. He was raising the spongy moths in his oak trees in his backyard and they got out, and they've been out ever since.ŌĆØ

Since then, the moth has spread as far west as Minnesota and as far south as North Carolina, according to the . Outbreaks can be dramatic and devastating to forests. Ridge remembers the first major outbreak she saw, in 1981.

ŌĆ£Cars were sliding on the roads because so many caterpillars were moving, and trains were actually having trouble stopping on the tracks because they were sliding on the caterpillars. It was just remarkable,ŌĆØ she recalls. ŌĆ£Entire areas of ║┌┴Ž│į╣Ž═° were completely defoliated. It looked like winter in June.ŌĆØ

Ridge says trees that lose their leaves to the caterpillars can end up in a battle for their lives.

ŌĆ£They're stressing the trees,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£And so if you have several years where trees have been fed onŌĆ” they're drawing this reserve of energy from their roots, and that lessens every year until the tree basically dies from exhaustion.ŌĆØ

In 1989, though, another non-native organism became a game changer in the fight against the spongy moth.

A killer fungus

The fungus Entomophaga maimaiga is from Japan, and itŌĆÖs unclear how it arrived in the spongy mothŌĆÖs range in North America. Anecdotally, Ridge says itŌĆÖs possible a ║┌┴Ž│į╣Ž═° scientist who had returned from a spongy moth-infested area in Japan brought it back on his boots. One thing was clear, though: the fungus was adept at killing spongy moth caterpillars.

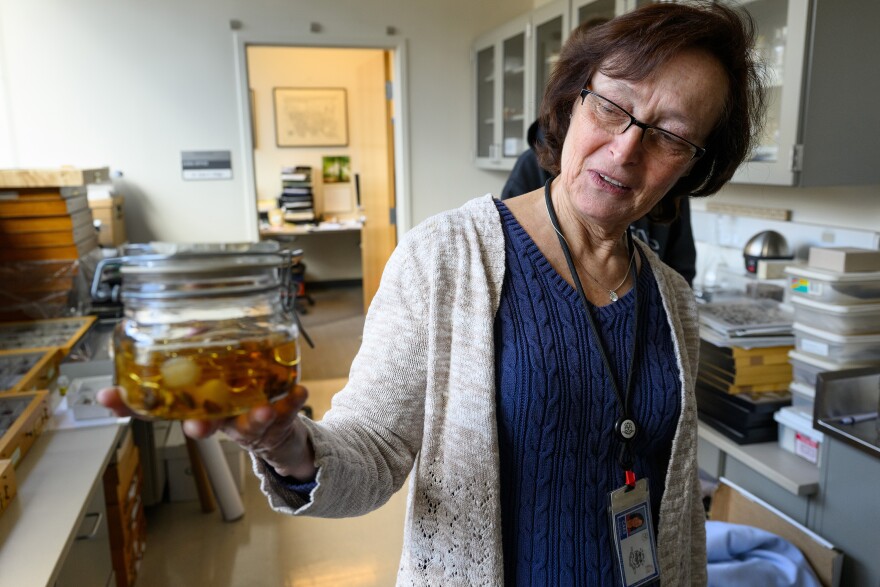

ŌĆ£When the caterpillars are infected with this, they die,ŌĆØ says Katherine Dugas, another entomologist at the experiment station. ŌĆ£They cling to the tree and they slowly liquefy. ItŌĆÖs pretty gruesome, but if you see it, thatŌĆÖs good news.ŌĆØ

The dead caterpillars on trees become ŌĆ£little spore factories,ŌĆØ Dugas says, spreading the killer fungus to their compatriots.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs lights out,ŌĆØ says Greg Dwyer, a professor of ecology and evolution at the University of Chicago. ŌĆ£Almost right away, starting in 1989, it started causing huge amounts of mortalityŌĆØ among spongy moth populations.

But the fungus needs the right weather to activate.

ŌĆ£If itŌĆÖs wet enough, the higher the relative humidity and if the temperatureŌĆÖs not too hot, then the pathogen will spread like wildfire, and it can wipe out a population of spongy moths in just a few weeks,ŌĆØ Dwyer explains.

Competing climate impacts

Climate change will likely play a big role in the extent to which the fungus will help control the spread of spongy moths in New England.

ŌĆ£Climate change is not just about polar bears not being able to walk out on the ice to hunt for seals,ŌĆØ Dwyer says. ŌĆ£Climate change is about oak trees in people's backyards.ŌĆØ

Dwyer is the senior author of a January in the journal Nature Climate Change titled ŌĆ£Climate change drives reduced biocontrol of the invasive spongy moth.ŌĆØ

He and his team project that overall warmer and less humid conditions in the mothŌĆÖs range will lead to a decline in conditions conducive to activating and spreading the fungus, leading to greater defoliation of trees by spongy moth caterpillars.

ŌĆ£The effects of climate change on webs of interaction among species are hard to think through, and our research provides one glaring example of such an effect,ŌĆØ he says.

But Ridge, the ║┌┴Ž│į╣Ž═° entomologist, has hope. She notes springs in the northeast to see more precipitation due to climate change. Wetter springs, in theory, could lead to the activation of the fungus at the time of year when caterpillars begin to emerge from their spongy egg masses, from which the moth draws its name.

ŌĆ£Certainly, everything is going to be affectedŌĆØ by climate change, Ridge says. ŌĆ£The dynamics in our ecosystem are going to be shifting and changing and adapting as the weather dictates. Yes, spongy moth will certainly be affected ŌĆō IŌĆÖm hoping with wetter springs.ŌĆØ

ŌĆśAt the mercyŌĆÖ of a changing climate

It was a wet spring in 2023 that activated the fungus and curbed the spongy moth outbreak in Housatonic State Forest. Clark, the forester, remembers it well.

ŌĆ£We saw a huge kill-off of the caterpillars. There were dead caterpillars everywhere. It was gooey. It stank. But I was happy to see it nonetheless,ŌĆØ he recounts.

Looking to the future, Clark is unsure what to expect from a changing climate when it comes to spongy moth outbreaks and the health of the forest.

ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre kind of at the mercy of what the weather is going to give us,ŌĆØ Clark says. ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖve forecasted wetter springs, so that might activate the fungus. WeŌĆÖre also forecasted to have more droughty, drier summers, which could then further stress the trees out.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£So will that offset? Will it balance out?ŌĆØ Clark wonders aloud. ŌĆ£I think that just remains to be seen.ŌĆØ

Entomologists say thereŌĆÖs not a lot any of us can do, though some locals are getting creative in their attempts to save the oaks.

ŌĆ£One of the funniest anecdotes I was told by a landowner who had a significant amount of acreage was that he was collecting some of these [caterpillars infected by the fungus], putting them in a blender, making caterpillar soup, and then spraying it on his trees to basically spread the spores as far and wide as possible,ŌĆØ Dugas says. ŌĆ£I just thought that was a clever way to distribute this.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£You know, I'm not recommending that everybody sacrifice a blender,ŌĆØ Dugas says. ŌĆ£And do not mix up your smoothie-making blender with your caterpillar blender,ŌĆØ she adds.